Chapter 2 - Conceptual foundations

The first question that arises frequently—sometimes innocently and sometimes not—is simply, "Why model?" Imagining a rhetorical (non-innocent) inquisitor, my favorite retort is, "You are a modeler." (...) when you close your eyes and imagine an epidemic spreading, or any other social dynamic, you are running some model or other. It is just an implicit model that you haven't written down.

We need to cover some conceptual and philosophical grounds before we can start modeling. We’ll start by considering what models are for.

Why do scientists model?

There is not one answer to this question. There are many possible reasons and valid purposes for modeling. For instance, some models have the purpose to describe (or represent). Descriptive models typically capture some aspects of the thing described and ignore others. Often they maintain relational information about things in the world, while not necessarily respecting the scale of the thing described. A familiar example is the globe that you may have on your desk. This model is substantially smaller than the thing it models (i.e., earth), yet it describes quite accurately the relative shapes, borders and locations of countries, oceans and seas on the surface of the earth. Many details remain omitted of course.

Sometimes descriptive models ignore more than just the scale of things. The picture on the right depicting the relation between the planets and the sun in our solar system illustrates this idea. This picture ignores relative distances between planets and the sun and only captures their ordering.

Models need not be pictorial. For instance, we can also describe the ordering of the planets using functions, such as \(d(x,y)\) to denote the distance between \(x\) and \(y\); and using mathematical symbols, such as \(<\) for ‘smaller than’:

\(d(Mercury, Sun) < d(Venus, Sun) < d(Earth, Sun) < d(Mars, Sun)\) \(<d(Jupiter, Sun) < d(Saturn, Sun) < d(Uranus, Sun) < d(Neptune, Sun)\)

In this description even more information is lost. There is no longer any information about the relative sizes of the planets, nor about colours.Note that in the picture above the relative sizes of the sun and planets were in fact distorted (e.g., the Sun is many orders of magnitude bigger than Earth) and the colours of the planets are caricatures at best. Every model, qua description or representation, will omit information and distort on some dimensions. This is unavoidable, but we can be aware of it. Yet, the relevant information about ordering is perfectly retained. The type of models we will be developing in this book are more of the mathematical type than the pictorial type.

Do you think cognitive scientists and psychologists also make use of descriptive models?

What mathematical descriptive model could describe a person’s ability to add numbers?

What mathematical descriptive model could describe a person’s ability to multiply numbers?

As models minimally describe somethingThis need not be a real or concrete thing, but can also be a hypothetical thing. For instance, a globe could describe the geography of an alien planet in a sci-fi novel, and a mathematical model could describe a hypothesized cognitive ability. , they can be used for other purposes, too. For instance, the globe can be used to predict that if one starts sailing from the coast of The Netherlands and heads straight West, one will eventually bump into the coast of the United Kingdom. This prediction holds no matter where you start on the Dutch coast (provided you stay on course). To make a more precise prediction of where you most likely will end up, you would need more information about where you started on the Dutch coast (e.g., above or below the longitude coordinate of Zandvoort aan Zee).

Can we also use models to predict people’s behaviour? Sure. You do this all the time yourself. For instance, when you predict how someone will behave in a given situation, based on their past behaviour in similar situations, you are using a model of that personAnd a model of 'similarity'; a topic we will pick up in Chapter 7. . It is just not a model that you have written down (cf. quote at start of this chapter). Similarly, when you predict how someone will behave in a given situation, based on how other people behave in similar situations, you are also using a model. This second type of model is more generic and not specific to the person. A third possibility is when you predict how someone will behave in a given situation, based on how similar people have behaved in similar situations. Then you are using a model that is neither person specific, nor fully generic, but specific to a group of people who are similar (according to some dimension you assume is relevantcf. stereotypes. ).

Take a moment to think of concrete situations where you tried to predict a person’s behaviour. What type of model did you use, and why?

What could be an example of a model used by scientists to predict a person’s behaviour.

A third important use of models is to explain (or understand).

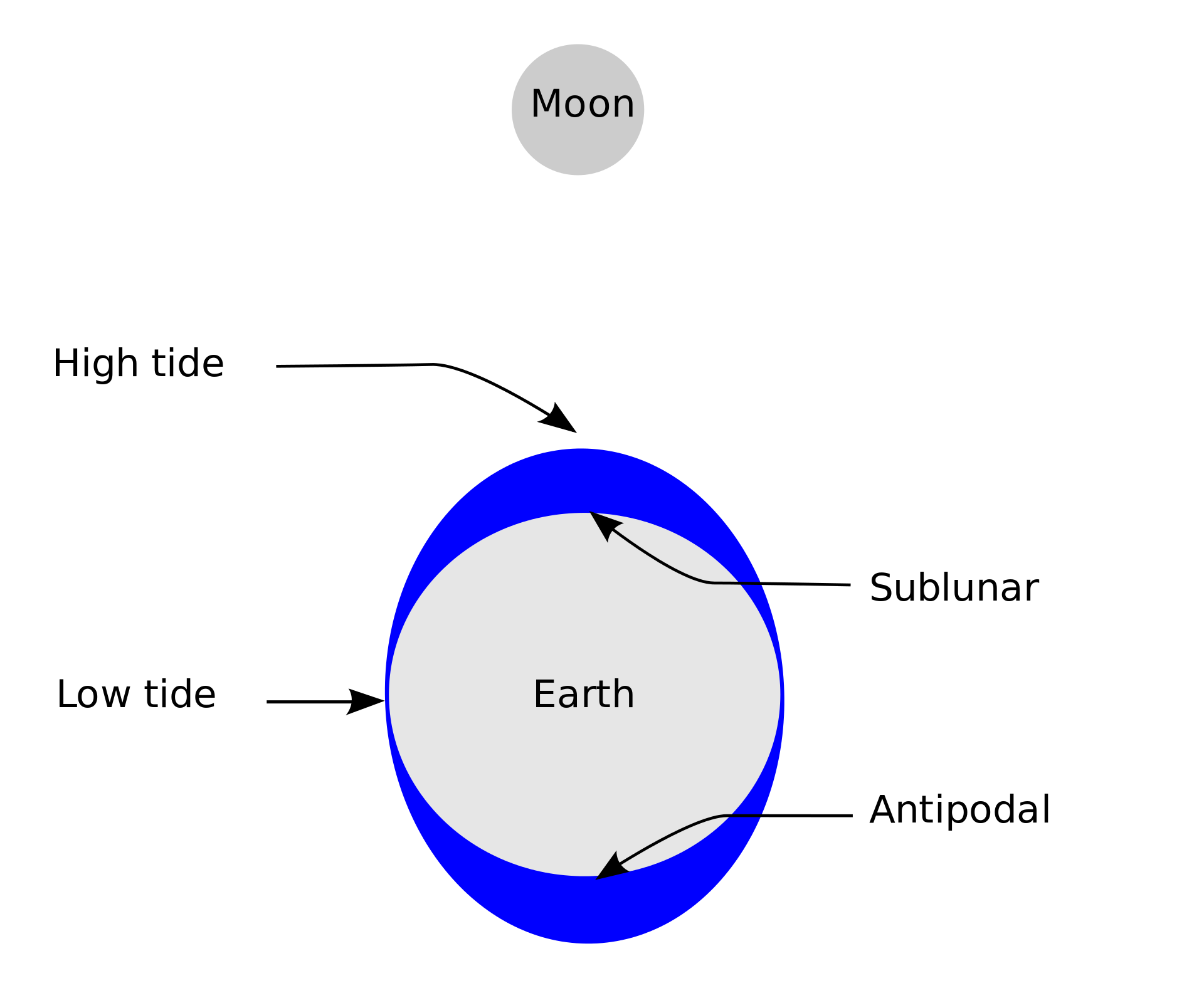

Schematic explaining the lunar tides. From Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 3.0. Models that explain can be seen as answering ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions. For instance, the schematic on the right can be used to explain why there are tides and how they come about: i.e., the gravitational pull of the moon generates a tidal force that causes Earth and its water to bulge out on the side closest to and farthest away from the moon. The solar tide works similarly, but is not shown in the schematic. For a more complete explanation watch this.

An important thing to notice is that models that predict need not explain, and vice versa. For instance, using tide tables you can very precisely predict the tides at any time of the day at different locations. Yet, tide tables do not explain the tidescf. Cummins (2000) . Similarly, we could construct a big look-up table to predict what types of products people tend to buy at different times during the year. Even if the table would make good predictions it would not explain why people buy more ice cream in Summer and more Christmas trees in December.Depending on where you are on Earth this may or may not be around the same time. Conversely, while the schematic model of the tidal force created by the moon generates understanding of the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of tides, it is too abstract to make very precise, local predictions about the tides. Similarly, a scientific explanation of the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of the human ability to make decisionsA topic we will pick up further in Chapter 4. is likely too abstract and generic to predict particular concrete choices that people make.

Besides describing, predicting and explaining, models can also be used for, say, controlling, prescribing, and emulating.

For instance, if one has a model of ‘consumer biases’ then this model could be used to figure out how to ‘nudge’ people into buying certain products; or, if one has a model of what causes depression then one could use the model to design a treatment that removes the cause. Both these examples would be instances of using a model to exert control over something, for better or worse. If one uses a normative model of reasoning (as in logic or probability theory) or deciding (as in economic choice theory) then the model could be used to prescribe how one should reason or should decide if one were to be rational. This type of prescriptive model need not be descriptive of actual human behaviour; though there exist psychologists and cognitive scientists who believe that prescriptive models can be descriptive in that sense, too.Chater & Oaksford (2000). The rational analysis of mind and behavior Synthese, 122, pp. 93–131. Lastly, we could make a model of human cognition and instantiate it in an artificial agent (e.g., a physical robot or virtual agent). Then the model would serve to emulate (or simulateWhether or not intelligence can really be emulated, and not just merely simulated, is a longstanding debate in AI (see strong versus weak AI). ) the thing modeled. The idea that models can be made to emulate human cognition has of course led to the foundation of the field artificial intelligence (AI). Similarly, the idea that models can be made to emulate natural evolution has founded the field of artificial life.

So far we have offered several possible reasons for modeling. Can you think of more?

Explaining capacities

All possible purposes for modeling are valid. One use is not better than another. All depends on one’s scientific aims. In the remainder of this book we will focus on modeling with the scientific aim of explaining or otherwise advancing our understanding of (cognitive) psychological phenomena (though other uses of modeling may show their faces along the way insofar as they support this aim). This can also include models that try to explain but fail to do so. As you will see, we can learn as much from model ‘failures’ as from model ‘successes’, or from modeling ‘hypotheticals’ and ‘counterfactuals’. But before we dive into modeling, let’s think deeply about what it is that we want our models to explain.

“(…) a substantial proportion of research effort in experimental psychology isn’t expended directly in the explanation business; it is expended in the business of discovering and confirming effects” – Cummins (2000). For psychologists and cognitive scientists whose day-to-day research involves doing experiments in the lab and analysing data, a first obvious contender for ‘target explananda’Terminology: explanandum (plural explananda) means the thing to be explained, and explanans means the thing doing the explaining, i.e. the explanation. Theoretical modeling is different from (statistical) data modeling. This may prima facie look odd for cognitive and psychological scientists used to analyzing empirical data. We will be modeling target phenomena, not data. may be one or more of the ‘effects’ established via such research practices. Take for instance, well-known effects like the Stroop effect, the McGurk effect, the primacy and recency effects, visual illusions etc. Aren’t these the things we should be explaining? Not really. Or rather, not primarily. While effects have a role to play in the scientific enterprise they are at best secondary explananda for psychologal and cognitive science. Ideally, we do not construct theories just to explain effects. The Stroop effect, the McGurk effect, the primacy and recency effects, visual illusions etc. rather serve to arbitrate between competing explanations of the capacities for cognitive control, speech perception, memory, and vision, respectively. It is these kinds of capacities that form the primary explananda.

A capacity is a dispositional property of a system at one of its levels of organization: e.g., single neurons have capacities (firing, exciting, inhibiting) and so do minds and brains (vision, learning, reasoning) and groups of people (coordination, competition, polarization). A capacity is a more or less reliable ability (or disposition or tendency) to transform some initial state (or 'input') into a resulting state ('output').

Tides and rainbows are two of the many natural phenomena we can all observe and don't require intricate methods to be discovered. Unexplained these phenomena are puzzling. The same holds for many cognitive capacities, like decision making and communication, and many others.

Primary explananda are the key phenomena that collectively define a field of study. For instance, cognitive psychology’s primary explananda are the various cognitive capacities that humans and other animals seem endowed with. These include capacities for learning, language, perception, categorization, decision making, planning, problem solving, reasoning, communication, to name a few. While effects (secondary explananda) are often only discovered through intricate methods and experiments, capacities (primary explananda) usually need not be discovered in the same way. We often know roughly the kinds of capacities we’d like to explain before we bring them into the lab. How else could we know there was something to study in the first place?

Just like we knew about tides (or rainbows, nordic lights, thunder and lighting, etc.) from naturalistic observation before seeking explanations for these puzzling phenomena, so too we already know that humans can learn languages, interpret complex visual scenes, navigate dynamic and uncertain environments, and have conversations with conspecifics. These capacities are so remarkable and difficult to explain computationally or mechanistically that we do not know yet how to emulate them in artificial systems at human levels of sophistication. Like the tides, rainbows, etc., these cognitive capacities are puzzling and demand explanation.

How do we explain capacities?

According to the influential tri-level framework proposed by David Marr (1982) capacities can be analyzed at three different levels: the computational level, the algorithmic level, and the implementational level. At the computational level, we ask the question, ‘what is the nature of the problem solved by the capacity?’ An answer to this question comes in the form of a hypothesized input-output mapping, a.k.a. computational problem. At the algorithmic level, we ask: ‘how is the input-output mapping that characterizes the capacity computed?’ An answer to this question comes in the form of a hypothesized algorithm, a step-by-step procedure computing the hypothesized mapping. And finally, at the implementational level, we ask: ‘how is the algorithm physically realized?’ An answer to this question comes in the form of a specification of how the algorithm posed at the algorithmic level is hypothesized to be implemented in the ‘stuff’ realizing the capacity.

An important feature of Marr’s framework is that lower levels of explanation are underdetermined, though constrained, by the higher levels of explanation: A function can, in principle, be computed by different algorithms; and any given algorithm can, in principle, be physically realized in different ways. Let’s illustrate these ideas using a capacity called sorting (e.g., one can order people from youngest to oldest, order choice options from least to most preferred, etc.). We will adopt the conventionThis convention comes from computer science. We believe that adoption of this convention in psychology and cognitive science will bring more clarity about the scope and commitments of computational-level theories. In the current literature, these aspects often remain implicit or ill-defined, causing crosstalk and making explanatory failures invisible (more on this in Part II of this book). that a computational-level model can be represented as follows:

Name of modelled capacity

Input: Specification of the input.

Output:

Specification of the output as a function of the input.

For the capacity sorting, this looks as follows:

Sorting

Input: A list of unordered numbers \(L\).

Output:

An ordered list \(L'\) that consists of the elements in \(L\).

In other words, here we stipulate that \(L'\) = Sorting\((L)\). For instance, if \(L\) is 625739 then \(L'\) is 235679.

The Sorting function can be computed by different algorithms. For instance, one strategy can be to consider each item, from left to right, to find the smallest element in the list \(L\), and put it in position 1 of list \(L'\). Then repeat this for the remainder of the numbers in \(L\), and put the next smallest number in position 2 in list \(L'\); and so on, until one has filled up list \(L'\) using the elements in \(L\). A different strategy, however, could be to order the numbers in \(L\) by ‘swapping’ adjancent numbers: i.e., consider the numbers in position 1 and 2 in \(L\), and if the second number smaller than the first then swap the two numbers. Repeat for the numbers in position 2 and 3, positions 3 and 4, and so on. Then repeat the whole procedure starting again at position 1, and repeat until no more swaps can be made.

Both algorithms, called selection sort and bubble sort respectively (Knuth, 1968), compute the Sorting function. Besides these two algorithms there exists a host of different sorting algorithms, all of which compute exactly the same function, though their timing profiles may differ.For a visual and auditory illustration of 15 distinct sorting algorithms watch this. Like the Sorting function can be computed by different algorithms, each algorithm can be realized in different physical ways. For instance, a sorting algorithm can be physically realized by a computer or a brain, or even as a distributed group activity (e.g., by people walking though a maze (van Rooij & Baggio, 2020), or by a group of Hungarian dancers.Here an example video for sorting through a maze, and an example video for sorting by Hungarian dancers.

An important lesson is that the levels of explanation of Marr do not correspond to levels of organisation.See also McClamrock (1991). That is, at each level of organisation we can ask the three questions: what is the computational problem? how is the problem computed? how is the algorithm implemented?

Following Marr (1982), in this book we adopt a top-down strategy. We focus on the computational level, but we will have things to say on algorithmic and implementational level considerations, especially in ways that they constrain computational-level theorizing (van Rooij et al., 2019) and vice versa (Blokpoel, 2018). The computational level of analysis is specifically useful as an interface between those aspects of psychology and cognitive science that focus on behavior and those aspects that focus on physical implementation (e.g., neuroscience or genetics) as it casts cognitive and other psychological capacities in an abstract common language of computation.

Further Reading

Cognitive science has a long tradition of theoretical modeling due to the central role played by computer theory, theoretical linguistics, and philosophy in the birth of this multidiscipline in the 1950s (a.k.a. the ‘cognitive revolution’; Miller, 2003). Other parts of psychological science historically show more neglect of theory and modeling.A notable exception is mathematical psychology (Navarro, 2021). However, there are initiatives to bring more awareness of the limits of science without theoretical modeling (Guest & Martin, 2021: Muthukrishna & Henrich, 2019; Smaldino, 2019, van Rooij & Baggio, 2021).See also the recent Special issue on Theory in Psychological Science in the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Much has been written on Marr’s 3 levels, critiques as well as reformulations (see, e.g., McClamrock, 1991). To learn more about the diversity of views on Marr’s levels we recommend reading the special issue in Topics in Cognitive Science titled Thirty Years After Marr’s Vision: Levels of Analysis in Cognitive Science.

References

Blokpoel, M. (2018). Sculpting computational-level models. Topics in Cognitive Science, 10(3), 641–648.

Cummins, R. (1985). The Nature of Psychological Explanation. MIT Press.

Cummins, R. (2000). How does it work?” versus” what are the laws?”: Two conceptions of psychological explanation. In Explanation and cognition (pp. 117–144). Frank C. Keil, Robert Andrew Wilson (Eds). MIT Press.

Guest, O., & Martin, A. E. (2021). How computational modeling can force theory building in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Epstein, J. M. (2008). Why model?. Journal of artificial societies and social simulation, 11(4), 12.

Knuth, D. E. (1968). The art of computer programming: Sorting and Searching. Addison-Wesley.

Pages 69-73 from: Marr, D. (1982). Vision: A computational investigation into the human representation and processing of visual information. New York.

McClamrock, R. (1991). Marr’s three levels: A re-evaluation. Minds and Machines, 1(2), 185-196.

Miller, G. A. (2003). The cognitive revolution: a historical perspective. Trends in cognitive sciences, 7(3), 141-144.

Muthukrishna, M., & Henrich, J. (2019). A problem with theory. Nature Human Behaviour, 3, 221–22.

Navarro, D. J. (2021). If mathematical psychology did not exist we might need to invent it: A comment on theory building in psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Smaldino, P. (2019). Better methods can’t make up for mediocre theory. Nature, 575(7781), 9-10.

van Rooij, I., & Baggio, G. (2021). Theory before the test: How to build high-verisimilitude explanatory theories in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

van Rooij, I., Blokpoel, M., Kwisthout, J. & Wareham, T. (2019). Cognition and Intractability. Cambridge University Press.