Chapter 4 - Formal proofs

In the previous chapter we introduced different mathematical frameworks that alllow us to formally define theoretical models. This allows us not only to precisely communicate the theory, but it also affords further analysis of the theory. For example, we can use formal proofs to derive implications of our theoretical commitments. In this Chapter, we present a brief primer on formal proofs. The concept of a formal proof may sound intimidating and may evoke images of walls of math. However, it is good to remind ourselves that in essense a formal proof is nothing more than an argument to convince another person that a property is true, relative to our theoretical assumptions. In fact, the roots of formal proofs can be traced back to our ability to dialog or debate (Dutihl Novaes, 2020).

Readers who have taken introductory classes on these topics can skip this chapter without loss of continuity. If, however, these materials are new to you, then we recommend carefully studying this chapter before proceeding.

Introductory example

Before we explain the history of formal proofs and specific proof techniques, let’s review an example proof to get an impression of what a formal proof entails. In Chapter 2 - Conceptual foundations we informally introduced the notion of sorting.

Sorting (informal)

Input: A list of unordered numbers \(L\).

Output:

An ordered list \(L'\) that consists of the elements in \(L\).

Using the math notations from Chapter 3 we can now make sorting formal. Note that we are adding more details, for example the relationship between the numbers in \(L\) and \(L'\) and the notion of ordered is formally specified.

Sorting (formal)

Input: A list of \(p\) unordered numbers \(L=\langle m_1, m_2, \dots , m_p \rangle\).

Output:

An ordered list \(L'=\langle n_1, n_2, \dots , n_p\rangle\). Here, each \(m_i\in L\) occurs exactly once in \(L'\) and for all consequitive pairs \(n_i, n_{i+1}\) the next number should be (strictly) bigger, i.e., \(n_i < n_{i+1}\).

Based on this theory, we may conjecture (i.e., think that it holds) that any list of numbers \(L\) can be sorted as specified by the theory.

Do you think that the conjecture is true or false? Why do you believe this? How would you convince someone else to accept the conjecture?

The conjecture, in fact, is not true, which can be shown by a counter example. Consider the input \(L=\langle 6, 3, 1, 3 \rangle\). From the formalization, each of the numbers should occur exactly once in \(L'\). However, no permutation of the numbers exists that satisfies the condition that \(n_i < n_{i+1}\), as we can observe in Table 1.

Table 1: All possible permutations of the numbers in \(L\).

| \(n_1\) | \(n_2\) | \(n_3\) | \(n_4\) | Is ordered? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | < | 3 | < | 3 | < | 6 | no, \(3\nless 3\) |

| 1 | < | 3 | < | 6 | < | 3 | no, \(6\nless 3\) |

| 1 | < | 6 | < | 3 | < | 3 | no, \(6\nless 3\) |

| 3 | < | 1 | < | 3 | < | 6 | no, \(3\nless 1\) |

| 3 | < | 1 | < | 6 | < | 3 | no, \(3\nless 1\) |

| 3 | < | 3 | < | 1 | < | 6 | no, \(3\nless 1\) |

| 3 | < | 3 | < | 6 | < | 1 | no, \(3\nless 3\) |

| 3 | < | 6 | < | 1 | < | 3 | no, \(6\nless 1\) |

| 3 | < | 6 | < | 3 | < | 1 | no, \(6\nless 3\) |

| 6 | < | 1 | < | 3 | < | 3 | no, \(6\nless 1\) |

| 6 | < | 3 | < | 1 | < | 3 | no, \(6\nless 3\) |

| 6 | < | 3 | < | 3 | < | 1 | no, \(6\nless 3\) |

This proves by illustration (or counter example) that a list exists that cannot be sorted, because none of the possible permutations is ordered. Hence, the conjecture must be false. This realization may lead to another conjecture: If the list \(L\) contains a number twice, then no sorted list \(L'\) can exist. This conjecture cannot be proven by example as we cannot possibly show all lists that contain a number twice, there are infinitely many of them.

Do you think that the second conjecture is true or false? Why do you believe this? How would you convince someone else to accept the conjecture?

While we cannot list all possible lists that contain a number twice, we can say something about all those lists. Namely, each such list at minimum must contain a pair of the same number \(n_i, n_j \in L\), where \(n_i=n_j\). The best place in the output \(L'\) to place these two numbers, is next to each other, where the numbers before \(n_i\) are ordered and the numbers after \(n_j\) are also ordered:

\[L'=\langle n_1, n_2, \dots, n_i, n_j, \dots, n_p\rangle\]However, the list cannot be sorted, because \(n_i\nless n_j\) and \(n_j\nless n_i\). Thus we must conclude that any list that contains a number twice cannot be sorted.

What to learn from the example?

The constructions of formal proofs is a creative skill, from the sprouting of conjectures to the formal proofs themselves. While there are formal rules and constraints that are navigated, there is no procedure that one can follow to derive a formal property or prove it. With practise and experience, intuitions can be sharpened that will help constructing formal proofs. A further perspective to consider is that proofs are intended to convince others of a particular point, they are arguments. Sometimes an argument requires more formal details, other times a sketch can be convincing enough. Think of the formal nature of a proof not as an obstacle, but rather as a way to strengthen theoretical arguments.

We next cover some of the fascinating history of formal proofs, after which we illustrate three commonly used formal proof strategies.

History of formal proofs

Similarly to math and formal notation, the long history of formal proofs often is lost in the shadow of more recent (western) approaches. Yet, formal proofs, formal reasoning and logic have a long history dating back to hundrends of years BC all across the world such as China, India, Eqypt, Babylon, Ancient Greece and the Syria. Even a short summary of this history would require volumes of books. Here, we highlight several important discoveries in the history of formal proofs so that we may appreciate that our current work is supported by a long tradition that spans millenia and many diverse cultures and people.

India

Rig Veda, 10:129-6:

नासदासीन्नो सदासीत्तदानीं नासीद्रजो नो व्योमा परो यत्।

किमावरीवः कुह कस्य शर्मन्नम्भः किमासीद्गहनं गभीरम्॥१॥

न मृत्युरासीदमृतं न तर्हि न रात्र्या अह्न आसीत्प्रकेतः।

आनीदवातं स्वधया तदेकं तस्माद्धान्यन्न परः किं चनास॥२॥

तम आसीत्तमसा गूळ्हमग्रेऽप्रकेतं सलिलं सर्वमा इदम्।

तुच्छ्येनाभ्वपिहितं यदासीत्तपसस्तन्महिनाजायतैकम्॥३॥

कामस्तदग्रे समवर्तताधि मनसो रेतः प्रथमं यदासीत्।

सतो बन्धुमसति निरविन्दन् हृदि प्रतीष्या कवयो मनीषा॥४॥

तिरश्चीनो विततो रश्मिरेषामधः स्विदासी३दुपरि स्विदासी३त्।

रेतोधा आसन्महिमान आसन्त्स्वधा अवस्तात्प्रयतिः परस्तात्॥५॥

को अद्धा वेद क इह प्र वोचत्कुत आजाता कुत इयं विसृष्टिः।

अर्वाग्देवा अस्य विसर्जनेनाथा को वेद यत आबभूव॥६॥

इयं विसृष्टिर्यत आबभूव यदि वा दधे यदि वा न।

यो अस्याध्यक्षः परमे व्योमन्त्सो अङ्ग वेद यदि वा न वेद॥७॥

In ancient India, the Buddhist Madhyamaka school founded by नागार्जुन Nāgārjuna (Sanskrit) (c. 150 – c. 250 CE) used the catuṣkoṭi (Sanskrit), a way to systematically analyze a proposition \(P\). It includes four mutually exclusive possibilities for \(P\) (for a modern interpretation, see Jayatilleke, 1967):

(1) \(P\); that is, being.

(2) not \(P\); that is not being.

(3) \(P\) and not \(P\); that is being and that is not being.

(4) not (\(P\) or not \(P\)); that is neither not being not is that being.

The catuṣkoṭi is a logical tool, but its origins can be traced back even further to the Rig Vega (1500-1000 BC), an ancient collection of sūktas. The first verse, as translated by Kramer (1986) illustrates the origins of the catuṣkoṭi:

There was neither non-existence nor existence then;

Neither the realm of space, nor the sky which is beyond;

What stirred? Where? In whose protection?

China

In the Chinese 墨家 Mohist tradition founded by 墨翟 Mozi (c. 470 BC – c. 391 BC) logic and argumentation are based on analogies rather than mathematical reasoning. In Mohism the concept of fa is a standard or model, in a broad sense (e.g., fa could be a role model such as a teacher). They used the three fa method for statements by which “the distinctions between ‘this’ and ‘not’ and benefit and harm…can be clearly known” (Book 35, “Rejecting Fatalism”; Fraser, 2023).

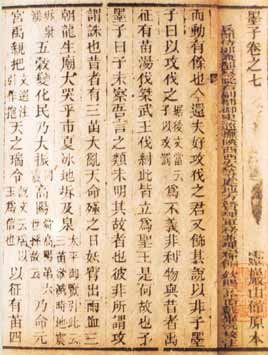

Text from 7th volume of Mozi (墨子卷之七).

(1) Does the statement have for precidence and origin?

(2) Does the statement show a concern for empiricism?

(3) Is the statement of consequence and pragmatic utility?

It is important to realise that these methods for reasoning were used in philosophical, societal and political contexts. The three fa were used by the Mozi for the benefit of the people and society (Fraser, 2023).

Greece

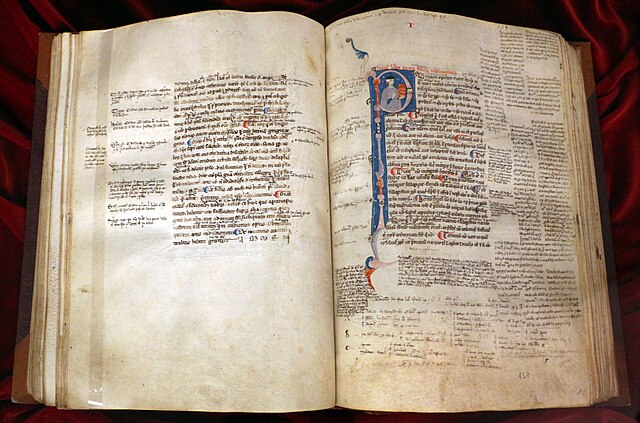

Aristotle's Prior Analytics in Latin, 1290 circa, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence.

Perhaps most recognizable to people trained in western philosophy are the contributions to logic and mathematics by Greek scholars (between c. 520BC – 200 BC) such as Pythagoras, Plato and Aristotle. Aristotilian logic is believed to be the first attempt at formal logic with syntax and used variables to show the form of an argument independent of the matter. Aristotle defined a syllogism (an argument) in his book Prior Analytics as consisting of predicates and a conclusion (Aristotle, 1989):

(1) Predicate: \(A\) belongs to \(S\) (e.g.,

(2) Predicate: \(A\) is predicated of \(S\)

(3) Conclusion: \(A\) is said of \(S\)

This formal system allowed Aristotle, for example, to deal with contradicitions in a systematic way (Bochenski, 1970).

Syria

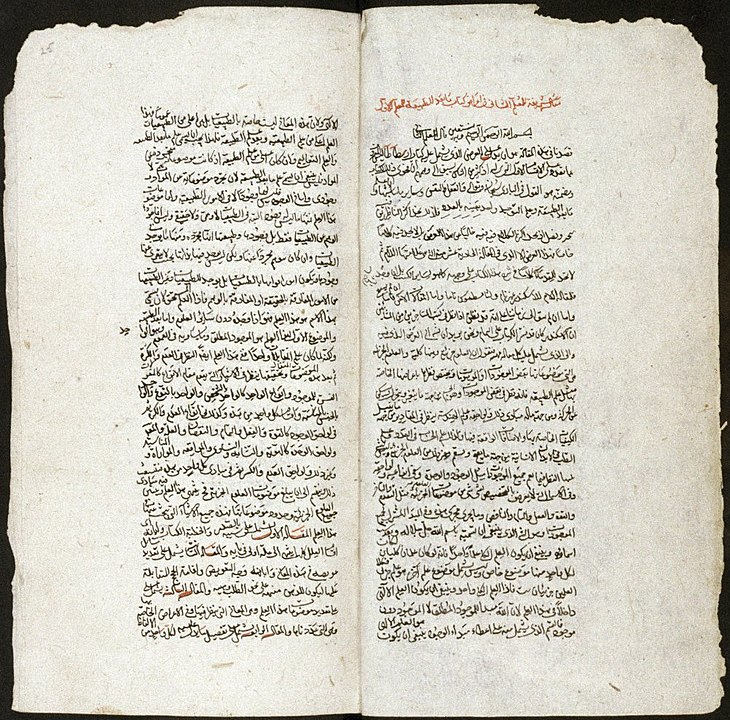

Pages from Maqala fi aghrad kitab Ma ba'd al-tabi'a (On the scope of Aristotle's Metaphysics) The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, Shelfmark: MS. Arab. d. 84.

In the 9th century, the Islamic philosopher أبو نصر محمد الفارابي (Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi) made major contributions to logic. He built on Greek works such as Aristotilian logic and the Stoic tradition. He argued that logic follows a dialogical structure:

Truth is found in answer and query, or jawab wa-su’al. In this, there is a mas’ul, one who is asked because he has promoted a thesis for which he is responsible, and there is a sa’il, an interrogator, who attempts to question this thesis.

Among the many contributions to logic, he was the first to categorize the notion of Takhayyul (idea), and of Thubut (proof) in his book Ihsaal-ulum (Enumeration of the Sciences) (Alwali, 2018).

Proof strategies

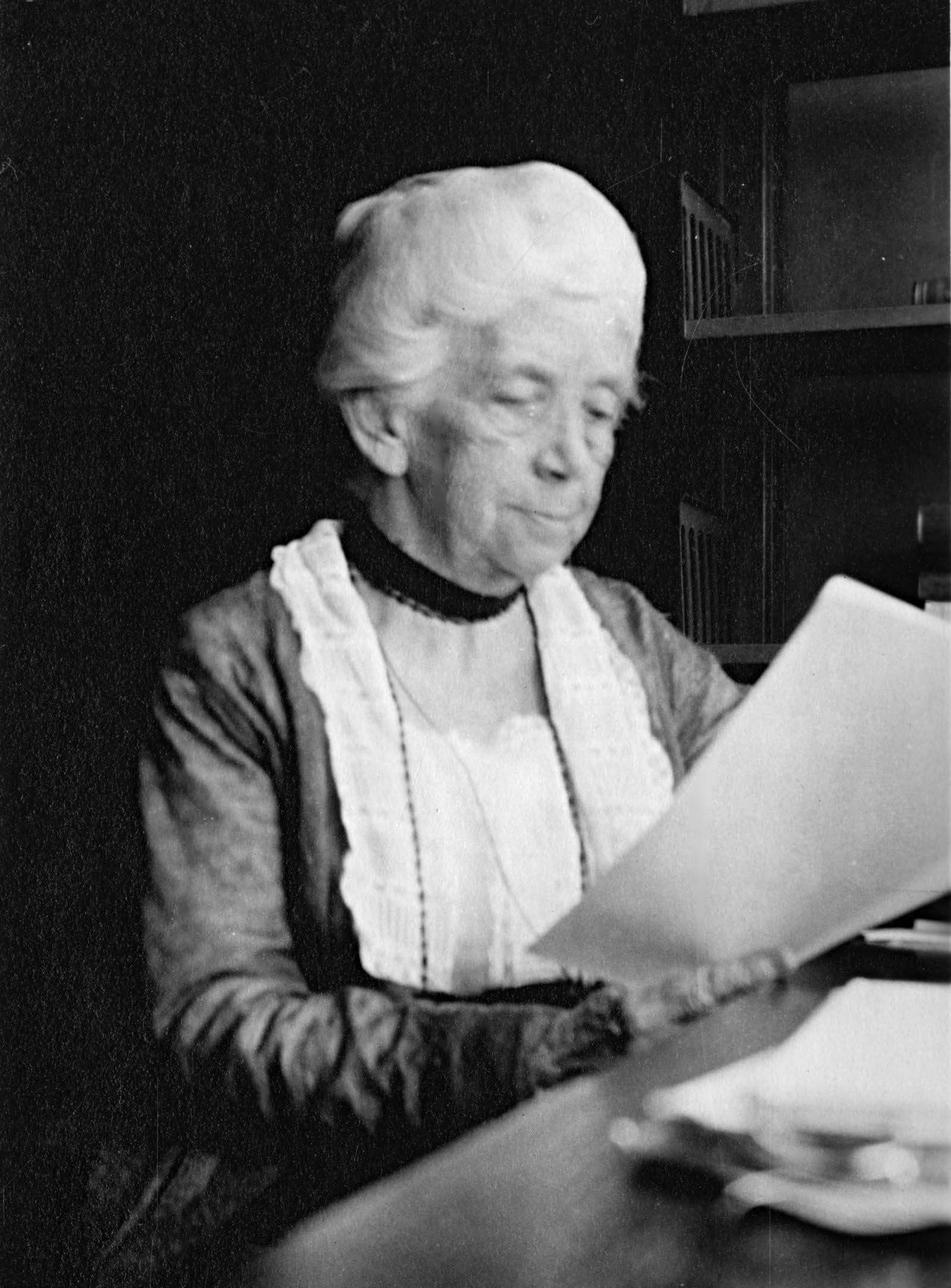

Rarely do we come up with proofs in the exact formal structure that we write them down.The proof strategies we present here are syllogisms. Other strategies exist, thought, such as the antilogism developed by Christine Ladd-Franklin (1847-1930) (Ladd-Franklin, 1883). The antilogism is the argument of discussion-of rebuttal:

“Nobody eats soup with a fork, Emily,” her mother said to her.

“But I do, and I am somebody,” Emily immediately replied.

‒ Shen (1927), p. 60

Christine Ladd-Franklin was the first woman to receive a PhD in mathematics and logic, 44 years after she wrote her thesis.

Often, proofs start with intuitions as shown in the example from the introduction. It takes experience and practise to sharpen your intuitions. The next three sections illustrate three common proof strategies with several examples and exercises to help you built your intuitions. Unfortunately, there is no procedure we can teach you to derive a proof. If we could, then finding formal proofs could be efficiently automated, whereas finding proofs is intractable or worse uncomputable.Intractable means that is takes astronomical resources to compute for all but the smallest cases (van Rooij, 2008; van Rooij et al., 2019). E.g., sorting is tractable and can be efficiently computed, but finding a proof could take more time than the age of the universe. If something is uncomputable it means with no amount of resources can it be computed, it is fundamentally impossible.

Often, proofs start with intuitions as shown in the example from the introduction. It takes experience and practise to sharpen your intuitions. The next three sections illustrate three common proof strategies with several examples and exercises to help you built your intuitions. Unfortunately, there is no procedure we can teach you to derive a proof. If we could, then finding formal proofs could be efficiently automated, whereas finding proofs is intractable or worse uncomputable.Intractable means that is takes astronomical resources to compute for all but the smallest cases (van Rooij, 2008; van Rooij et al., 2019). E.g., sorting is tractable and can be efficiently computed, but finding a proof could take more time than the age of the universe. If something is uncomputable it means with no amount of resources can it be computed, it is fundamentally impossible.

Proof by illustration

In the example from the Introduction we showed how a proof by illustration can be used to prove that any list with two or more times the same number cannot be sorted, when ‘sort’ is defined as the next number being strictly greater than the one before. In general, proof by illustration is useful to prove a statement some property \(P\) holds for all cases or for some cases. For example, in the illustration we claimed that all possible lists can be sorted (formally: \(\forall_{l\in L}\text{canBeSorted}(l)\)). Another example statement could be that some lists cannot be sorted (formally: \(\exists_{l\in L}\neg\text{canBeSorted}(l)\)). Proof by illustration can prove two things:

(1) The falsity of universal statement \(U\equiv\forall_x P(x)\); prove that \(U\) is false by giving one case \(x\) for which \(P\) is false

(2) The truth of existential statement \(E\equiv\exists_x P(x)\); prove that \(E\) is true by giving one case \(x\) for which \(P\) is true

We’ve seen an illustration of (1) in the example in the Introduction. What about the option (2)? We can apply proof by illustration to the existential statement that some lists cannot be sorted (formally: \(\exists_{l\in L}\neg\text{canBeSorted}(l)\)), given the formalization of sorting in the Introduction.

Direct proof

A direct proof consists of building an argument with a particular structure, namely a sequence of statements that themselves are either axiomatic (foundational), assumed to be true, or follow logically from an earlier statement. The final statement in this sequence is the statement we want to prove to be true. In a sense, a proof by illustration is a strategy that can be used in a direct proof. Let’s make the second proof in the Introduction a bit more formal. In the proof sketch we implicitly assumed formal definition of sorting, we assumed the illustration list, then we showed that the conclusion must follow from the definition and the illustration. We can structure this as the following sequence of statementsWe use the list structure here for pedagogical reasons, to convey the structure of a direct proof. In practise, formal proofs are more often written in narrative form, ideally supported with figures and examples. :

(1) Assume: Sorting (formal);

(2) Assume: \(L=\langle 6,3,1,3\rangle\);

(3) Infer: From 1 and 2 that the sorted list must be in the set of all possible permutations of \(L\);

(4) Infer: From 1 and 3 that each permutation must contain a pair of the same number \(n_i, n_j \in L\), where \(n_i=n_j\);

(5) Infer: From 1 that the only place in the output \(L'\) to place \(n_i\) and \(n_j\), is next to each other;

(6) Infer: From 1 that for the list to be sorted, the numbers before \(n_i\) should be ordered and the numbers after \(n_j\) should also be ordered: \(L'=\langle n_1, n_2, \dots, n_i, n_j, \dots, n_p\rangle\);

(7) Infer: From 1, 5 and 6 that the list \(L=\langle 6,3,1,3\rangle\) cannot be sorted, because \(n_i\nless n_j\) and \(n_j\nless n_i\);

(8) Conclude: From 5, 6 and 7 that that any list that contains a number twice cannot be sorted.

In a direct proof, one can use any formally sound inference to infer a statement. However, as illustrated in the Introduction, proof sketches can already be convincing. A further formal analysis such as the sequence above may help to further sharpen one’s proof.

Direct proof examples

Let’s review another direct proof, one that is not a proof by illustration. Consider the statement: “The square of an odd integer \(n\in \mathbb{N}\) is odd.”

(1) Assume: An integer \(n\) is odd if \(n=2\cdot k + 1\), for some integer \(k\);

(2) Assume: The square of \(n\) is \(n^2=n\cdot n\);

(3) Infer: From 1 and 2 that \(n^2=n\cdot n=(2\cdot k + 1)\cdot (2\cdot k + 1)\);

(4) Infer: From 3 and rewriting the formula that \(n^2=n\cdot n=(2\cdot k)^2 + 2(2\cdot k) + 1\);

(5) Infer: From 4 and rewriting the formula that \(n^2=n\cdot n=4k^2 + 4k + 1\);

(6) Conclude: From 1 and 5 that \(4k^2 + 4k\) is an integer and \(n^2\) is odd.

Direct proofs need not be arithmetic, they can be applied to other mathematical formalisms too. Take logic, for example. Consider the following proof:

(1) Assume: Predicate \(r \rightarrow a\): If you are a reader of our book, we appreciate you;

(2) Assume: Proposition \(r\): You are a reader of our book;

(3) Conclude: From 1 \(r\) and 2 \(r\rightarrow a\) we infer \(a\), we appreciate you.Just to be sure, this does not prove that we do not appreciate people who do not read our book. Although they will never read this.

Indirect proof

You may have wondered that if a direct proof exist, then what is an indirect proof? Indirect proofs do not go straight from assumptions to conclusions, but rather prove a statement in a different manner. There are several indirect proof strategies, here we illustrate one: Proof by contradiction.

In logical inference, contradictions are not allowed. Something cannot be true and false at the same time.This assumption is called law of excluded mean, a proposition must be true or false. Prof. Alice Ambrose (1906-2001), presents a thorough analysis whether or not 'the law of excluded mean [is] valid universally' (p. 186; Ambrose, 1935) which she relates to 'the question whether the verbal forms [of formal predicates] are actually values of “p or not-p”' (p. 199; Ambrose, 1935).

For example, I cannot be alive and dead at the same time. Anytime that a proof (which formally follows logical inference) leads to a contradiction, we have to conclude that one of our assumptions was incorrect and the opposite must hold. If we want to prove \(P\) is true, then in a proof by contradiction we start by assuming not \(P\). Intuitively, this looks like this:

For example, I cannot be alive and dead at the same time. Anytime that a proof (which formally follows logical inference) leads to a contradiction, we have to conclude that one of our assumptions was incorrect and the opposite must hold. If we want to prove \(P\) is true, then in a proof by contradiction we start by assuming not \(P\). Intuitively, this looks like this:

Say we want to prove \(P\): We appreciate some people. We prove by contradiction and hence assume not \(P\): There are not some people we appreciate, i.e., we do not appreciate all people. We also assume, like before, that we appreciate readers of our book and that you are reading our book. Now we have a contradiction, we do not appreciate you because we do not appreciate all people, but we appreciate you because you read our book. Hence, we must conclude that our assumption of not \(P\) is incorrect and we have to accept that we appreciate some people.

If we want to write this down in a list of statements, it would look like this:

(1) Assume: We do not appreciate some people \(\neg\exists_{p\in P}\text{appreciate}(p)\) which is equivalentThe negation of the existential quantifier is equivalent to the universal quantifier with the negated proposition: If there are no people that we appreciate, we must not appreciate all people. to we do not appreciate all people \(\forall_{p\in P}\neg\text{appreciate}(p)\);

(2) Assume: Predicate \(r \rightarrow a\): If you are a reader of our book, we appreciate you;

(3) Assume: Proposition \(r\): You are a reader of our book;

(4) Infer: From 1 \(r\) and 2 \(r\rightarrow a\) we infer \(a\), we appreciate you;

(5) Contradiction: 1 and 4 are in contradiction, we both appreciate and not appreciate you;

(6) Conclusion: From 5 we conclude that the assumption in 1 must be incorrect, and we accept its opposite: We appreciate some people \(\exists_{p\in P}\text{appreciate}(p)\).

Proof by contradiction example

Let’s also look at an example. Consider the following formalization called Vertex Cover, a classical graph problem from computer science (van Rooij et al., 2019). A vertex cover takes as input a graph and outputs a subset of vertices that covers all edges.

An example instance of Vertex Cover, with vertex set \(V = \{A, B, C, D, E \}\). \(A\) is shown to cover edges \((A, B), (A, C), (A, D)\).

Vertex Cover

Input: A graph \(G=(V, E)\).

Output:

An subset of vertices \(V'\subseteq V\) such that all edges \(e\in E\) are covered. Here, \(e=(u, v)\), and being covered means that either \(u\in V'\) or \(v\in V'\) (or both).

Take your solution or the one from above and flip the selected vertices, i.e., if a vertex is red make it white and vice versa. What do you observe? Why is this the case?

The vertices in the complement of a vertex cover \(V'\) have no edges between them, i.e., they are what is called an indepentent set. Can we prove that the complement set of a vertex cover is an indepentent set using a proof by contradiction? Let’s start by assuming some definitions:

(1) Assume: Vertex Cover and a cover \(V'\);

(2) Assume: An indepentent set is a set of vertices that have no edges between them in graph \(G\);

(3) Assume: The complement of a subset \(A\subseteq V\) contains all the other elements in the set \(A^C=V\setminus A\);

Then we assume the opposite of what we want to prove, namely that the complement of a vertex cover is not an independent set. That means we assume that there is an edge between at some pair of vertices in the complement.

(4) Assume: The negation of what we want to prove, namely that the complement \(V'^C\) of a vertex cover \(V'\) has at least one edge between a pair of vertices \((u,v)\in V'^C\);

(5) Infer: From 4 we infer that if \(u\) and \(v\) are in the complement set, then they were both not in the vertex cover;

(6) Infer: From 5 we infer that if \(u\) and \(v\) were not in the vertex cover, then the edge \((u,v)\) is not covered;

(8) Conclude: From 7 we must conclude that one of our assumptions is incorrect. Assumptions 1, 2, and 3 are foundational (i.e., definitions), so we reject 4 and conclude that the complement of a vertex cover must be an independent set.

References

Alwali, Abduljaleel (2018). Logic Functions in the Philosophy of Al-Farabi in Handbook of the 6th World Congress and School on Universal Logic.

Ambrose, Alice (1935). Finitism in Mathematics. Mind, 44(174), pp. 186–203. doi:10.1093/mind/XLIV.174.186.

Aristotle (1989). Prior Analytics (Robin Smith, Trans.). (Original work work published c. 350BC)

Bochenski, Joseph M. (1970). A History of Formal Logic. Chelsea Publishing Company.

Dutilh Novaes, Catarina (2020). The Dialogical Roots of Deduction: Historical, Cognitive, and Philosophical Perspectives on Reasoning. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108800792.

Fraser, Chris (2023). Mohism in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta, Uri Nodelman (eds.) (URL)

Jayatilleke, Kulatissa Nanda (1967). The Logic of Four Alternatives. Philosophy East and West, 17(1/4), 69–83. doi:10.2307/1397046.

Kramer, K. (1986). World Scriptures: An Introduction to Comparative Religions. Paulist Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-8091-2781-4.

Ladd-Franklin, Christine (1883). On the algebra of logic. In C. S. Peirce (Eds.), Studies in logic (pp. 17-71), Little, Brown, Boston.

Shen, Eugene (1927). The Ladd-Franklin Formula in Logic: The Antilogism. Min 36(141), pp. 54-60.

van Rooij, Iris (2008). The Tractable Cognition thesis. Cognitive Science, 32, 939-984.

van Rooij, Iris, Blokpoel, Mark, Kwisthout, Johan, Wareham, Todd (2019). Intractability and Cognition: A guide to classical and parameterized complexity analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.